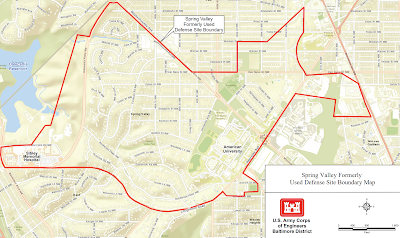

The century-old legacy of a U.S. Army chemical weapons testing site in Northwest Washington, D.C. continues to haunt the Spring Valley community. A major remediation project to locate and remove World War I-era munitions - and the toxic chemicals and compounds they contain - from soil in the residential neighborhood is drawing to a close. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has now released its first Five-Year-Review (FYR) of the project and its results, a thick document nearly 300 pages in length. Written in a highly-technical format rather than clear prose for the common man, and accessible via a lengthy URL found in a small announcement in the back pages of the Washington Post Sports section, the document has received no news coverage and likely few readers among the public. Here are a few points that jumped out in my review of the review, as well as some of the images and graphs I thought local readers might find most interesting:

First is a mission statement as to the purpose of the report, which suggests - correctly - that the whole munitions problem in Spring Valley hasn't magically disappeared with the wave of a magic wand.

"The FYR has been prepared due to the fact that hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants remain at the site above levels that allow for unlimited use and unrestricted exposure (UU/UE)." (Page 6)

|

| Some of the munitions debris recovered from sites across Spring Valley |

This determination stands in contrast to the USACE cleanup at the "Hole called Hades," a burial pit filled with munitions and toxic waste hidden under a residential lot at 4825 Glenbrook Road NW. The home on the site was demolished, munitions and contaminants excavated, and the soil removed down to the bedrock. The USACE has now deemed that empty lot permissible "for unlimited use and unrestricted exposure (UU/UE)."

|

| Photo from an unidentified street in the report |

But despite the remediation work that has been done throughout the Spring Valley neighborhood, the USACE cannot make a similar blanket statement for the whole community. That's because there are many parcels of land that, for physical reasons, inspectors could not investigate. For example, there could still be munitions with explosive potential and chemical agents buried under homes or driveways, which could be encountered in the future. The USACE has advised all residents of this, and provided educational materials about what to do if residents or construction contractors encounter unexploded munitions.

|

| USACE informs residents of the "3Rs" of munitions safety, should they encounter any remaining ordinance in the future |

The report notes the limitations that were inherent in the search for munitions and contaminants hidden below ground in the community:

"Magnetometer data were used to identify potential burial pits or caches of munitions at depths of up to 8-

to 10-ft below ground surface (bgs). Geophysical coverage was not achieved over 100% of these areas

due to accessibility issues either due to vegetation or structures blocking coverage. The geophysical

survey identified over 28,000 subsurface metallic anomalies and selected 3,155 anomalies for intrusive

investigation." (Page 12)

to 10-ft below ground surface (bgs). Geophysical coverage was not achieved over 100% of these areas

due to accessibility issues either due to vegetation or structures blocking coverage. The geophysical

survey identified over 28,000 subsurface metallic anomalies and selected 3,155 anomalies for intrusive

investigation." (Page 12)

One of the most interesting aspects of the Five-Year-Review is that the number of munitions or remnants of weapons, and of contaminated areas, was far higher than previous public discussions suggested. The finds scattered across the neighborhood and Dalecarlia Parkway corridor were located on a whopping 92 properties. 91 of those 92 property owners allowed the USACE to recover all accessible materials, and complete a remediation effort.

The munitions found that fit the criteria to be considered "munitions and explosives of concern (MEC)" included a 3-inch Stokes mortar shell, a Livens projectile, and a 3-inch smoothbore cannonball. The cannonball was determined "to pose an explosive hazard." Intriguingly, the cannonball was also determined to not be related to the World War I-era testing, but to be of the Civil War era.

In terms of contaminated soil that remains to be remediated, the report cites multiple findings of cobalt residue on a residential property on Woodway Lane, adjacent to American University, and not far from the Hades Pit. In sufficient amounts, cobalt is known to be toxic to plants, animals and humans, and is a carcinogen. The FYR details the specific locations around the exterior of the home where the cobalt was detected and is to be removed. When this work, and further remediation at the American University Public Safety Building site, are complete, the USACE will consider the remediation effort finished.

The USACE has uploaded an interesting video that gives a brief summary of the munitions story, as well as detailing the "3Rs" that residents or excavation workers should follow if they encounter these weapons in the future.

This has been a traumatic, life-changing event for those who have suffered health impacts from the contamination. For even more Spring Valley residents, it has been a source of worry and great inconvenience. Hopefully, the worst is now in the past.

Spring Valley remains one of the top places to live in the area, the country, and - arguably - the world, in my opinion. Large, solid homes with the classic architecture and landscape-preserving layouts W.C. & A.N. Miller is famous for, a commercial area with top restaurants that has retained its historic low-rise character, and a well-organized community that has been able to fight off the kind of urbanization efforts many neighborhoods in Montgomery County have been victimized by over the last decade.

|

| Cobalt finds on the "Spaulding-Raskin Exposure Unit" site on Woodway Lane |

|

| Cobalt samples taken at the Spaulding-Raskin Exposure Unit site |

Photos courtesy USACE, except top image by AI

Am hoping all the mitigations have worked. I'm old enough to remember old timers calling it Death Valley and we as kids used to play a drain area called Devil's Bathtub. Not dead yet. I do wonder, however, where 100 years of groundwater have moved most of those contaminents. I'm sure it's somewhere in the hydrological reports yet I am not that motivated to search through them. If anybody knows where those containments would have moved to, please post. Thank you.

ReplyDelete